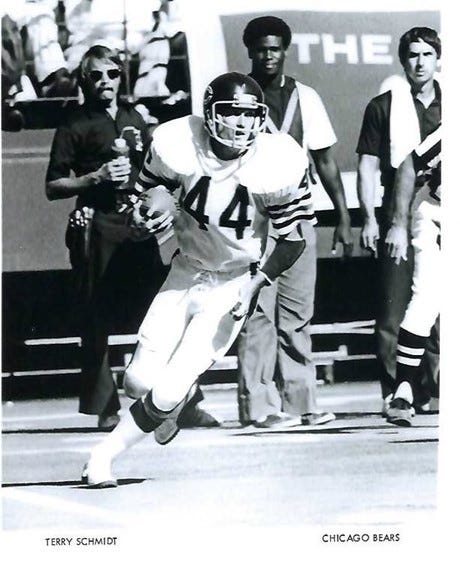

Being a professional football player was never Terry Schmidt’s goal. He wanted to be a dentist.

But there Schmidt was, on the field in Houston, staring at Earl Campbell, who was churning toward him.

‘He broke free,’ says Schmidt, a former NFL defensive back in the 1970s and 1980s, ‘and it was me and the end zone or Earl.’

Schmidt recalls hitting the future Hall of Fame running back on the 10-yard line, and getting him to the ground at the 2.

‘I think, even with that, I was having fun,’ Schmidt recalls today. He lets loose a hearty laugh, which reappeared several times during our conversation.

Schmidt lasted 11 years, retiring after 143 games in the league, and playing his final season for the 1984 Bears. That’s right, he missed winning a Super Bowl on one of the best – if not the best – NFL teams of all time.

He doesn’t regret the decision for a moment. His response as to why winds you through a brutal training camp with a future Hall of Fame coach but happier days at Chicago’s Soldier Field, and to the Amazon and Africa.

Schmidt laid out his life in football, and his one as a father to two kids.

‘My son was playing Little League baseball and he loved baseball, but they selected an all-star team, (and) the guy that coached, his son was a catcher, too, and my son never played,’ Schmidt told USA TODAY Sports. ‘We were driving home from a game and he said, ‘Dad why doesn’t that guy like me?’ And I didn’t have an answer for that and then he quit playing baseball. He just gave it up and it was a shame because he was a really good baseball player.’

We spoke with Schmidt, 73, about how his insight through a lifetime of experience can help you and your young athlete:

(Questions and responses are edited for length and clarity.)

‘I can really do this’: When we’re supported in sports, we’re full of confidence

Terry grew up in Columbus, Indiana, about 40 minutes south of Indianapolis. He loved open-wheel racing, and played high school basketball games in some of the old arenas you see in the movie ‘Hoosiers.’

‘My dad never really said, ‘Let’s go play catch,’ ” he says. “But when I was at school, I’d see kids playing baseball and stuff and I got interested and just started playing. And he helped coach but it wasn’t like one of these things like, ‘Well you need to do this, you need to do that.’ It was just, ‘If you want to play, ‘Fine.’ ”

Schmidt became a three-sport athlete in high school (football, basketball, track) and played football at Ball State. He never dreamed how far he would go from there.

USA TODAY: How did you come to be a professional football player?

Terry Schmidt: I was recruited as a wide receiver. After my freshman year, the head coach was changed (to Dave McClain). I was pretty fast, I guess, and he said, “We’re really deep at wide receiver.’ So, I started at safety spring ball of my freshman year and played all four years as a safety, and played in the East West Shrine game. He said, “You could probably play professional football.” I said, ‘Coach, ‘I don’t know. I’m gonna be a dentist.’ I was drafted by New Orleans, Hawaii (World Football League) and Winnipeg (Canadian Football League).

I thought what the heck, I’m gonna just give this a shot. One of the first strikes ever in the NFL was 1974, and so they brought in a bunch of rookies, free agents, whatever, whoever wandered to cross the picket line. And so, the veterans didn’t come in until after third preseason game. I had a really, really good training camp, and I ended up starting as a rookie for the Saints at corner.

It just kind of happened. I would watch guys on TV, and I’d go, “I’m not that.” But then when I got to training camp and realized, I said, “Yeah, I can do this. I really can do this.’

An egomaniac coach holds a team back, even if you’re Hank Stram

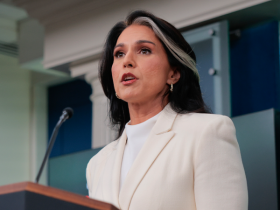

During his third NFL training camp, Schmidt found himself playing for Hank Stram, a future Hall of Fame coach who had led the Chiefs to an AFL championship and and a Super Bowl title.

“I think he was probably a great coach back when they won the Super Bowl, but as the players evolved, he didn’t evolve with them,’ Schmidt says.

After a wild training camp, the Saints traded Schmidt to Chicago before the 1976 season.

USAT: It’s a brutal game, right? I mean, every year was probably really tough to get through.

TS: In the NFL we did two-a-days and Stram, when he came in, we did three-a-days. The evening practice, it was 7-on-7; the linemen didn’t really do anything. So we were running all day long. By the time I got to the Bears, my legs were shot, they really were. Back in the day, players were conformist. When Stram first came to the Saints, that’s when they couldn’t stop you.

Stram was a good coach, but he was a egotist. We’d be on the bus, and once he got on the bus, everybody left. If you weren’t on the bus when Stram got on the bus, you got left behind. (If) the bus you were on tried to pass the bus Stram was on, he’d tell them to slow down. He had to be in the lead bus.

There was an article that came out in the (New Orleans) Times-Picayune that (owner) John Mecom said something about Stram spending too much money. The very next day, Mecom shows up at training camp and says, “I don’t know what you boys read, but I just wanted you to know that Hank’s my man and whatever Hank wants, Hank gets.” I was walking out after the meeting and I happened to be behind Mecom. I was gonna ask him something about (Indy) racing. I heard him turn to Stram and say, “Is that what you wanted me to say?”

Other tough coaches, like Mike Ditka, learn to compromise

Jim Finks, the Bears general manager, apparently had seen Schmidt play and liked him.

As an athlete, you never know who is watching you when you play, or whom you might run into down the road.

USAT: What happened with your career in Chicago?

TS: Allan Ellis, a great defensive back, got hurt right before the first game (of) the ’78 season. And I started playing at corner and never, ever turned back. We were playing a Thanksgiving game one time and by this time Stram had been fired (after going 7-21 over two seasons with the Saints) and I think he was doing radio for CBS. I happened to walk by Hank in this hallway, so I said, “Trading me was the best thing you ever did in my career.” And his response was, “Well, you know, Terry, we make mistakes from time to time.”

USAT: What were your experiences like with Ditka?

TS: In 1981, it was apparent (head coach) Neill Armstrong was going to be fired at the end of the season. We had made great strides as a defense under Buddy Ryan and as a defensive squad we collectively felt it would be best if the defensive staff remained. So we defensive players wrote a letter to (owner) George Halas, requesting he keep the defensive staff. About a week (later) he came to practice. Normally the whole team would gather around him. But today when the offensive players and coaches, including Neill, came to the group, Halas basically told them to “Beat it.”

He said the letter was beautiful and that to his knowledge no other group of players had ever written to attempt to save a coach’s job. Him being one of the founders of the NFL, that was most likely true. He told us not to worry, that Buddy and the staff would be retained.

So Mike had to keep Buddy, and his defensive system, when he was hired in 1982. Mike did always support the players, but sometimes I think it is difficult for great players to coach some players. Not all players had his play-through-anything (attitude) – pain, injury, etc. I heard he played with a very bad ankle sprain that was so intense it altered his running style, which led to hip problems (and) he eventually had it replaced. Some players did not share that same attitude.

Ditka (was a) complex individual, good coach, good man, very sarcastic at times. Interestingly, despite their differences, Mike came to Buddy’s funeral.

There’s always someone better than you, but you can always grow from an athletic experience

Schmidt would go in and talk to Ryan after the season. By 1984, he says, he was playing the game more mentally than physically.

“What do you think?” he asked Ryan.

“I think it’s time to plan your retirement party,” the coach said.

Schmidt had always planned on dental school, and he says the Bears had set aside money to pay for it over his last three contracts.

USAT: You just missed out on the ‘85 team. What was that like?

TS: You just never know. We made the playoffs in ’77 and ’79. And we got beat in the wild card. And then in ’84, we made it to the NFC Championship. So I figured, what’s the odds of them making it next year?

George Halas really embraced his boys – that they planned for the future, you don’t know how long you’re gonna play, or they’re always looking for somebody to replace you. So, when I asked for money for dental school, they had no qualms at all. The only restriction was that I had to go; they set aside about 50 grand and they just said you have to go to get it and that was fine with me.

And as I look back on my dental career in school, I don’t think I was mature enough for the rigors of dental school when I was 22 and 23. When I went to school, I was 34, and I had a lot of classmates who were just right out of undergrad. They were 22, 23, 24, and they just didn’t concentrate on school. I wanted to be the best dentist I could be. I was ready for the rigors of dental school. Because it’s like a job.

What we miss out on sometimes leads to a bigger opportunity

Schmidt became a dentist for the Department of Veterans Affairs. He worked in Chicago but also in Tampa, Florida, Asheville, North Carolina, and Johnson City, Tennessee, and continues his missionary work in retirement.

“One of the coolest trips we did was a boat trip on the Amazon River (that) stopped at five different villages,” he says. “Once you get up in the jungle where we were, you have a village that’s just carved out. You’ve got anywhere between 30 to maybe 80 homes, and everybody’s got a boat. Every house is up on stilts. And one house has a satellite dish and a generator so if Brazil’s in the World Cup, they get a chance to watch it. They call it football, but every village has got a soccer field and has got soccer balls.”

His kids, Jake and Jennifer, who are now adults, kept loving sports, too. They excelled at volleyball, and his daughter had speed and ran track, like her dad.

Jennifer’s son, Derek, plays rugby at Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama.

“It’s a brutal game,” his grandfather says. “They don’t wear any pads.”

USAT: Do you have any advice for families that are trying to go through all this with sports?

TS: I coached one year, and the parents … Why are you taking my kid out? What do you mean? We had a meeting with the parents and said, ‘Look, this is not professional baseball. These kids aren’t doing this for a living. We want to get everybody a chance to play.’

The one thing I didn’t like about volleyball is that one year Jennifer got involved in club volleyball, and that was a nightmare. They go all over the place and I just kept telling my kids, ‘You just can’t concentrate on one sport. If you want to, OK, but I’m just telling you, based on my history.’

Don’t push anything on your kids and have a piece of tape over your mouth. You don’t need to be yelling at the umpires, don’t be yelling at the coaches. Go there and enjoy your son or your daughter playing. And just just let ‘em play.

When I would get beat up, I was still having fun out there. If the first thought that goes through your head when Earl Campbell breaks free is, “I’m gonna get hurt,” you need to quit.

Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for two high schoolers. His Coach Steve column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.